Making Truly Great Noodles at Home

@Elvin Yung < @shikaku.ramen>

The “one weird trick” for making low-hydration noodles at home, without special equipment or imported ingredients

If you’re deep enough in the ramen rabbithole, you’ve probably heard some variant of this repeated: it’s really hard to make ramen noodles at home using just a pasta machine. You’ve probably heard that you can’t knead it like pasta and there’s not enough water to form the barely-hydrated crumbles into a workable dough, and that you need noodle machines that can exert tremendous amounts of pressure to turn those crumbles into a super dense dough. I would like to offer a second opinion.

I’ve adopted a simple process change that makes noodles with a bounciness, glossiness, and chewiness remarkably close to machine-made noodles in Japan. Not only does it consistently give better results, but it’s also easier than the existing standard method. By focusing first and foremost on building strong gluten, the dough actually becomes easier to work with even for hydrations as low as 27%. Moreover, this technique will help you make better noodles even if you do have a decent noodle machine at home.

I really do think that this is the “one weird trick” for homemade ramen, and I hope you’ll find it useful.

Why Pasta Rollers Suck For Ramen, and the Cheap Hack

The rollers on pasta machines and other home noodle machines (even motorized ones such as KitchenAid’s attachment), of course, are super weak compared to “true” noodle machines. They don’t exert enough pressure downward and inwards on the dough. This means that even if your hydration is perfect and your laminations are too, the gluten ends up instead being stretched outwards or even sheared apart as you roll it through, becoming too brittle before they get a chance to bind into a super dense network.

We can’t magically make the pasta roller stronger, but we can shape the dough in a more intentional way to help the process along. For that, we can look at another wheat noodle from Japan, a not-quite-cousin of ramen: udon.

In teuchi or handmade udon, just as in handmade ramen, there is an stage in which the crumbles get stepped down to form into a dough. But unlike ramen, udon places much more emphasis on the stepping stage: the dough is stepped, folded on itself, and then stepped again upwards of six times before rolling it out. For udon, in many ways this step is the gluten formation.

If you think a little bit more about how the gluten is formed here, it’s much closer to how noodle machines apply forces on dough: a lot of downward and inward pressure exerted on the dough compared to the lateral/fore-aft pressure that stretch it out (and weaken it).

The core insight is that you can apply this to lower-hydration dough as well: step more, roll less.

My Current Ramen Noodle Process

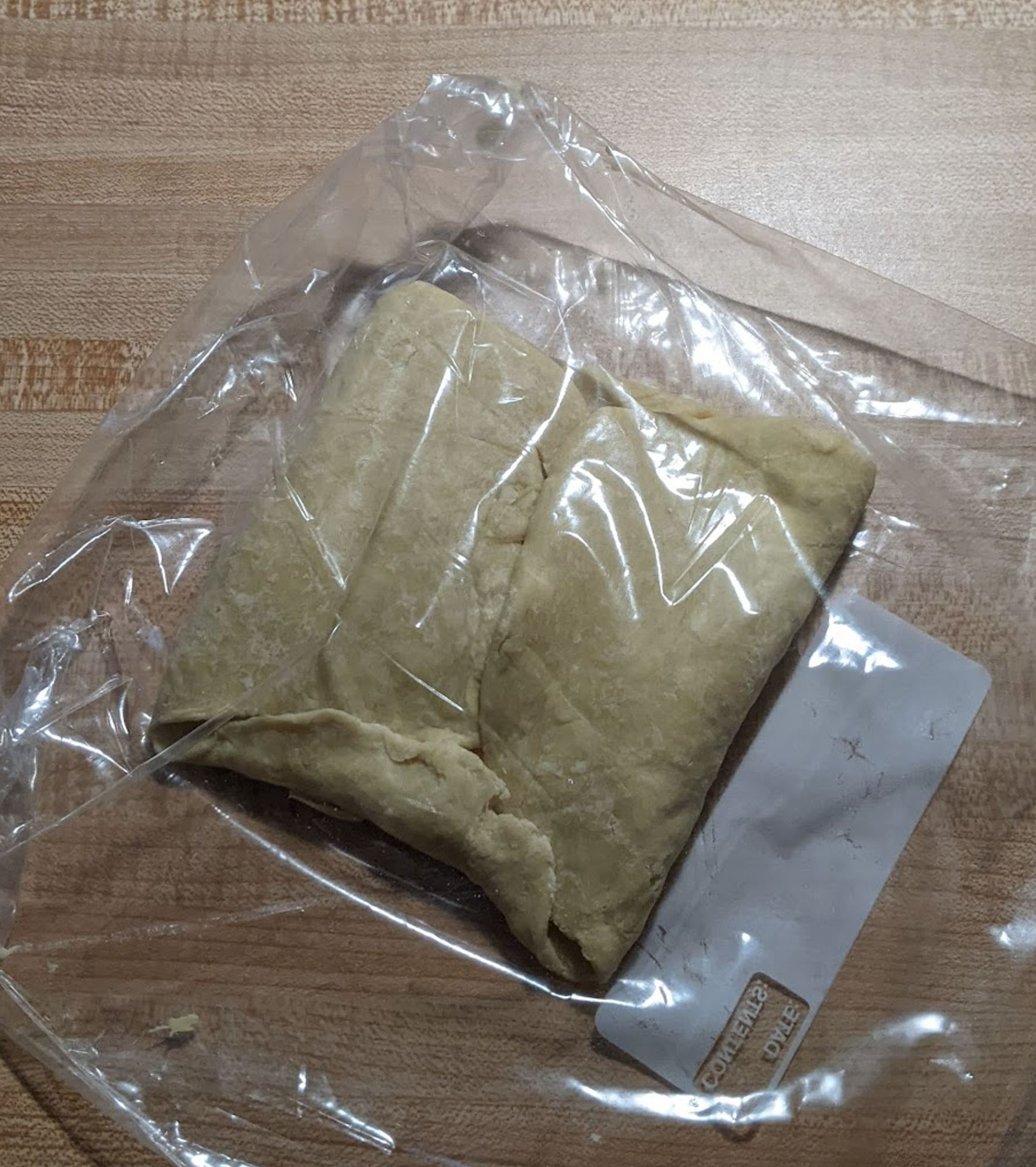

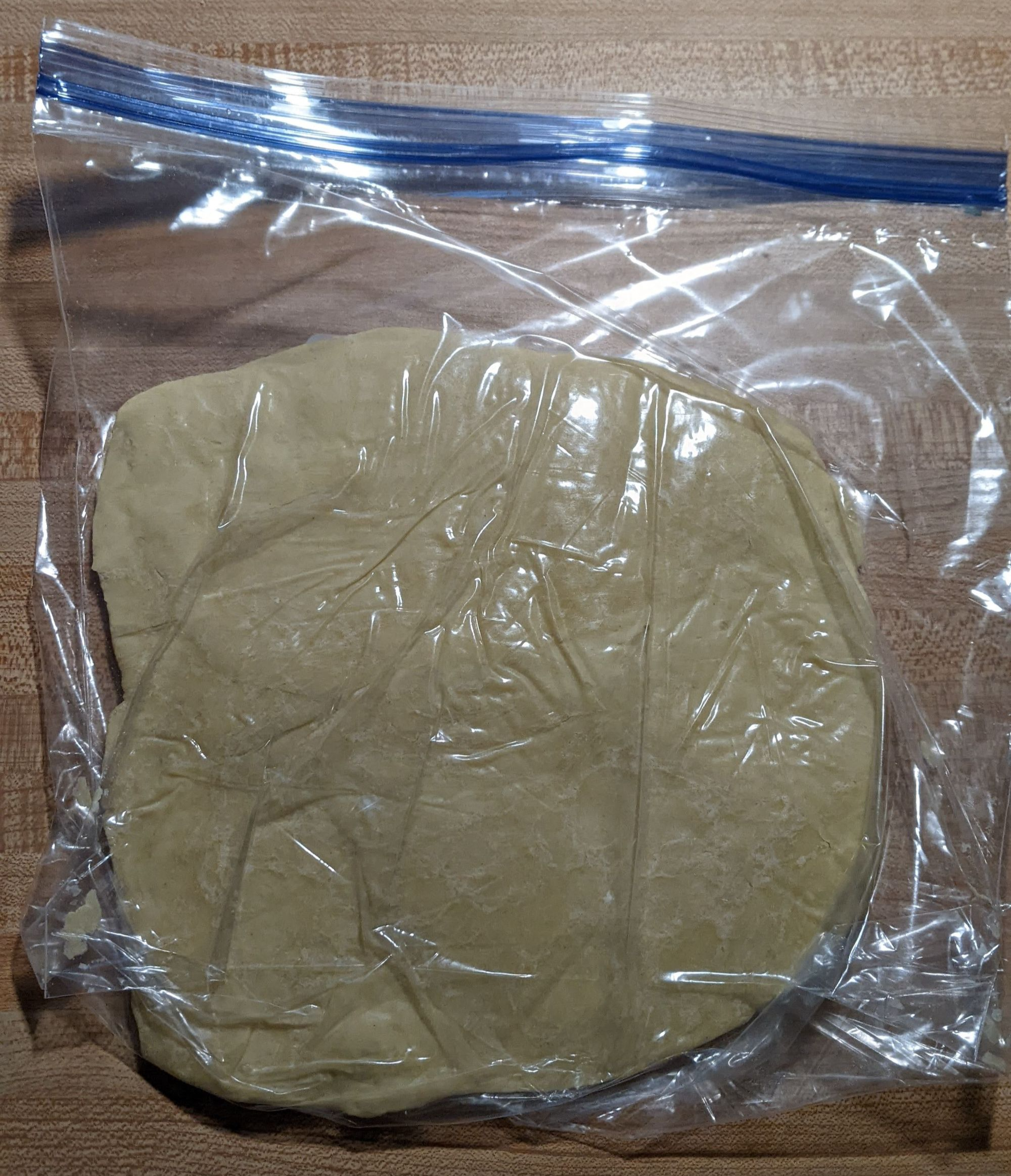

As far as I’ve tried, this method works with any hydration, any salt amount, and any kansui. Here’s a quick demonstration of the process with a basic 38% hydration dough. After mixing and resting the initial crumbles, pack them into a ziploc bag and rest it for about 15-30 minutes. We are then going to step and fold the dough multiple times before feeding it into a pasta roller.

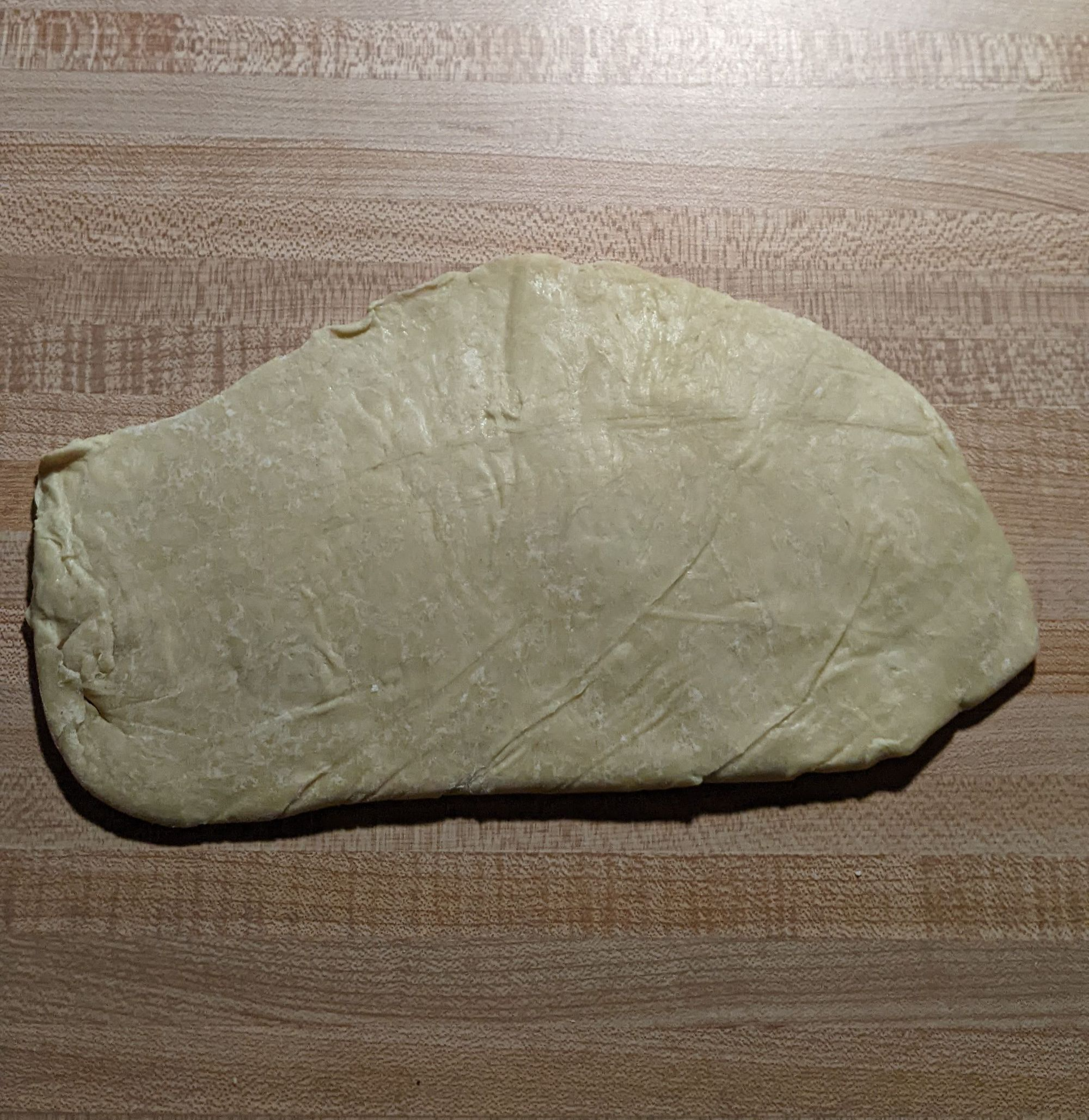

Each time you step, your dough should look something like this:

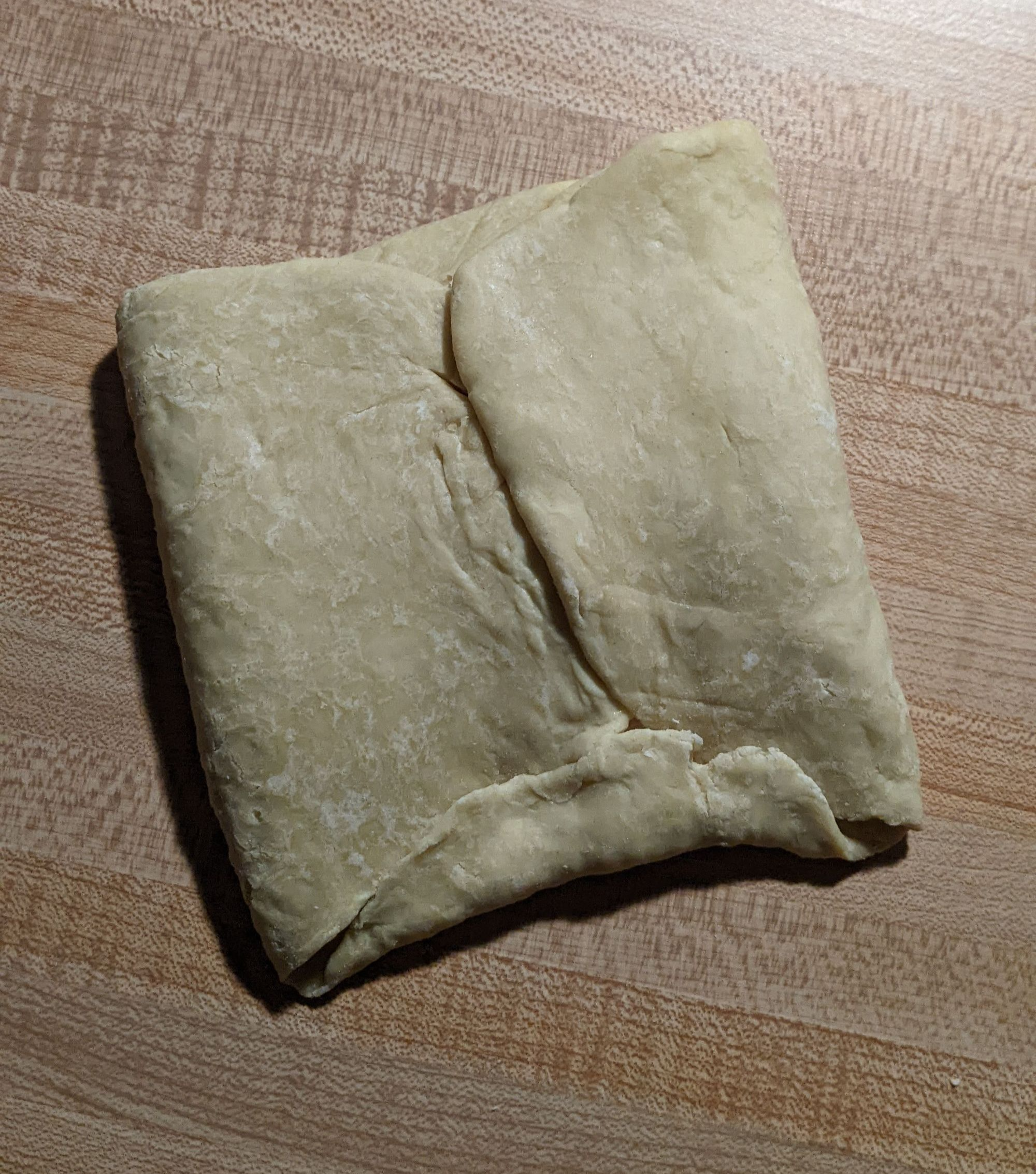

And then you just step again. And again, and again…

As you fold and step on the dough more and more, rather than becoming hard and brittle, it actually becomes bouncier and bouncier — completely unlike how it behaves when you roll it too many times on a pasta machine. How many times is right? I don’t think there’s a definitive answer — I’ve done anywhere between 3 to 8 steps, optionally with an additional rest in between, and my intuition so far says the ideal is at least 5 steps. (Note: udon intuition doesn’t apply exactly here, since the kansui does a lot to the dough.)

The next clip shows how the dough feels at around 6 steps. In total that’s mix, rest (still in crumble form), step, fold, step, fold, step, fold, step, fold, step, fold, step, then rest again, thin out, rest again, and cut. (”glorious nippon gluten, folded over 1000 times”)

After the dough feels bouncy enough, thin it out using a rolling pin first before feeding it into the pasta roller. Don’t be lazy here — even though the gluten is strong, the pasta roller is too weak to press a thick, densely-packed piece of dough, so it will tear the dough and maybe even break the roller if you try too hard. After thinning it out with the pin and the roller down to the appropriate size, (optionally) let the gluten rest again before cutting.

And that’s it!

Crazy Low Hydration Noodles + Glossy Noodles

One beneficial side effect of this trick is that a mix of almost any hydration level will form together into a resilient dough, after two or three steps. (I’ve tried as low as 27%.) It becomes much, much easier to make very low hydration noodle. They benefit from the stronger gluten too, with a more pronounced snappiness.

It also seems to help make noodles glossier and more translucent, without using starches or other adjuncts at all. I’m not ready to make a call on the importance of aging yet, but my current hypothesis (pure conjecture from what I’ve observed so far here) is that it’s a lot like making clear ice: you want to minimize trapped air bubbles and pockets of flour since they block light from passing through, and distributing moisture more evenly and building gluten more densely does that. In other words, translucency and glossiness are kind of like the windowpane test for noodles.

This method is also surprisingly scalable. There are udon shops in Japan that rely purely on this kind of process to make massive batches of noodles. You can mix and step on the dough as one massive piece, then portion it out and thin as necessary.

This might be presumptuous to say, but if there is truly any secret technique for making much better ramen, this may be it. Not only is it easier than existing ways to make noodles at home, but it also consistently creates a noodle that is glossier, bouncier, and chewier. Best of all, you don’t need any special noodle machine, Japanese flour, or any other equipment to use this technique — a rolling pin and a handcrank pasta machine will be more than enough for excellent noodles.

Sources and Further Reading

In-depth article about the concept of koshi (hard to translate, but roughly bounciness and chewiness) in noodles:

https://note.com/ramenreport/n/n9b55406a491d

https://note.com/ramenreport/n/n9b55406a491d

Detailed udon articles:

https://baikyoan.com/menkoza/udon/

https://baikyoan.com/menkoza/udon/

Thanks again to John, Preston Landers, Alex Zhao, Ben, Sho Spaeth, Tim Anderson, David Chan, Mike, and Sophia for reading this in draft form.

(part of the long-procrastinated Secret Pro Techniques ramen research series)